I have been playing with Ansible & Terraform to manage my infrastructure since early 2022. Both of these technologies have a bit of a learning curve, but in the last few months, I have found the pattern to allow me to expand the services that I run and how comfortable I am with how stable they are.

I am going to give a bit of an overview of how I use Terraform, Ansible and Docker (it’s not a particularly weird setup) and highlight some of the stuff which I like. To summarise, I use Terraform to create the infrastructure, Ansible to manage the infrastructure at the OS level and then Docker to run the services themselves.

Terraform Link to heading

Terraform is an Infrastructure-As-Code (IAC) tool that uses its own language, Hashicorp-Configuration-Language (HCL), to help manage all sorts of infrastructure from standard Virtual Machines to the more abstract cloud services like serverless products.

I really like how Terraform models the creation, altering and destruction of infrastructure. The flexibility of providers allows seamless management of resources across basically any cloud service but the Proxmox provider has also been fantastic for managing local VMs. I love how, with the relevant keys in a terraform.tfvars file, I can very quickly spin up any sort of resources in any of the clouds very quickly.

I also manage my public DNS records using the Namecheap provider, getting the records down in the declarative format effectively backs up my records and gives an inbuilt history in the Git log.

My only gripe is the need for a state file, this file keeps a snapshot of the infrastructure under Terraform’s control so that it can compare this to the live state of this infrastructure and identify anything it needs to do. I get why it is needed but it is something else to keep an eye on and when it gets locked (typically by doing something stupid) it can be a bit nerve-wracking to go in and force the unlock. I personally keep mine in an S3 bucket, a very easy and common thing to do but I thought I’d mention it.

Ansible Link to heading

Ansible is just great. There is a learning curve and there are patterns that you’re going to want to use, but the power that it can have is just nuts. I like to think of it as a higher-level remote scripting language.

Like Terraform, Ansible is a IAC tool but its whole model is different. Unlike Terraform, where a state file is used to identify required changes, Ansible observes the targeted machines to work out what it needs to do. If a step includes copying a file to the remote machine, Ansible will first check whether the same file already exists and, if it does, it doesn’t do anything. This is called being idempotent, a frequently cited strength of IAC tools. As such there isn’t any state file.

which machines? Link to heading

The machines you are controlling are stored in an inventory file, structured as a hierarchy of groups. This can be static, writing each hostname into each group, or dynamically. Below is a snippet of my main static inventory:

all:

hosts:

children:

local:

hosts:

tower.sarsoo.xyz:

phife.sarsoo.xyz:

insp.sarsoo.xyz:

cloud:

children:

linode:

azure:

dev:

docker:

hosts:

insp.sarsoo.xyz:

phife.sarsoo.xyz:

tower.sarsoo.xyz:

# graylog:

# hosts:

# tower.sarsoo.xyz:

jenkins:

hosts:

tower.sarsoo.xyz:Dynamic inventories feel a bit magic, to be honest, a separate inventory file can be responsible for AWS infrastructure and instead of listing each VM, Ansible uses the AWS API to get the currently live machines. These machines are included transparently in the inventory, a common pattern is to use the tags on these remote machines as the Ansible groups. This means that I can tag the groups that a machine should be part of in the Terraform and then this dictates the structure of my Ansible inventory.

roles Link to heading

I tend to map groups directly to roles, I imagine this is quite common. A role is a group of functionality - steps to be actioned, files to be copied - that tends to define a certain role that a machine will fulfil. You can see from the inventory snippet above that the tower will undertake the role of jenkins. The important bits of that jenkins role can be seen below,

- name: Create workspace

ansible.builtin.file:

path: $HOME/{{ jenkins_ws }}

state: directory

mode: '0755'

- name: Copy Service Spec

copy:

src: docker-compose.yml

dest: $HOME/{{ jenkins_ws }}/docker-compose.yml

owner: aj

group: aj

mode: u=rw,g=r,o=r

- name: Copy Root Cert

copy:

src: sarsooRoot.pem

dest: $HOME/{{ jenkins_ws }}/sarsooRoot.pem

owner: aj

group: aj

mode: u=rw,g=,o=

- name: Stand up service

community.docker.docker_compose:

project_src: $HOME/{{ jenkins_ws }}

pull: yesno more golden images Link to heading

Using a role named bootstrap which I can run on all of the inventory, I don’t use golden images anymore. A golden image is a template image that can be used to create a VM with pre-existing configurations like installed packages and packages. I had a handful of such images on Linode, but by using this role instead, I can effectively script out the steps that this image encompasses.

This has advantages and drawbacks but the main disadvantage would be speed. By pre-building this golden image, a VM built from it can start quicker than a bare image that then needs to be… gold-ened? gold-ified? The advantages are pretty powerful, however. Ansible can manage Linux, BSD and Windows, you can also make steps only run on specific operating systems or even more specifically, on different Linux distributions. With this, a well-crafted bootstrap can effectively be a gold-ifier that is cross-platform and cross-distribution.

Relying on the idemptotent strengths of Ansible, if there is a change to the gold role then this can be applied to all machines very quickly without needing to rebuild the golden images.

Docker Link to heading

Using containers to run services really makes life easy, particularly when using docker compose. It provides a separation from the OS with the service coming packaged with its dependencies so that the underlying OS can be updated independently. Using volumes to isolate the critical data for a service allows easier backup and makes it basically trivial to just destroy all remnants of the running code and be stood back up like nothing happened.

There are many other options to using vanilla docker (I’m including compose here) but it does the trick for me and my household. Kubernetes is incredibly powerful but it’s honestly overkill for what I need (although I do need to learn it). VMs can also be used for proper isolation but that is also a bit overkill for me and I don’t really have the compute resources to allow it. Running the services directly on the OS would be the other option and it would definitely be easier with Ansible, but the aforementioned separation from the OS is a real strength.

I’ve said a couple of times now that I use docker compose and it might be worth mentioning here that Ansible has a fantastic Docker module for all sorts of container operations that can basically replace compose. I do use this module for some operations but in terms of actually running the services I use compose files that I copy to the remote machine using Ansible. I like this for a couple of reasons, one of which is the readability of separating the service definition from the mechanics of starting the services themselves. It also means that I don’t need to use Ansible to manage the infrastructure once the role has been used once, I can remote into the box and use compose in the exact same way that Ansible is. A really cool use for this that I’ve found is that using iOS Shortcuts my phone will SSH into my PC and spin down Jenkins, Gitea and Jellyfin overnight before spinning them back up when my alarm goes off.

version: "3"

networks:

gitea:

external: false

volumes:

database-data:

services:

server:

image: gitea/gitea:1.19

container_name: gitea

env_file: .env

environment:

- USER_UID=1000

- USER_GID=1000

- GITEA__time__DEFAULT_UI_LOCATION=Europe/London

- GITEA__database__DB_TYPE=postgres

- GITEA__database__HOST=db:5432

- GITEA__database__NAME=gitea

- GITEA__database__USER=gitea

- GITEA__server__SSH_PORT=2222

- GITEA__mailer__ENABLED=true

restart: unless-stopped

networks:

- gitea

volumes:

- ./data:/data

- /etc/timezone:/etc/timezone:ro

- /etc/localtime:/etc/localtime:ro

ports:

- "3600:3000"

- "2222:22"

depends_on:

- db

db:

image: postgres:15

restart: unless-stopped

env_file: .env

environment:

- POSTGRES_USER=gitea

- POSTGRES_DB=gitea

ports:

- "3601:5432"

networks:

- gitea

volumes:

- database-data:/var/lib/postgresql/data

- ./backup:/backupMonitoring Link to heading

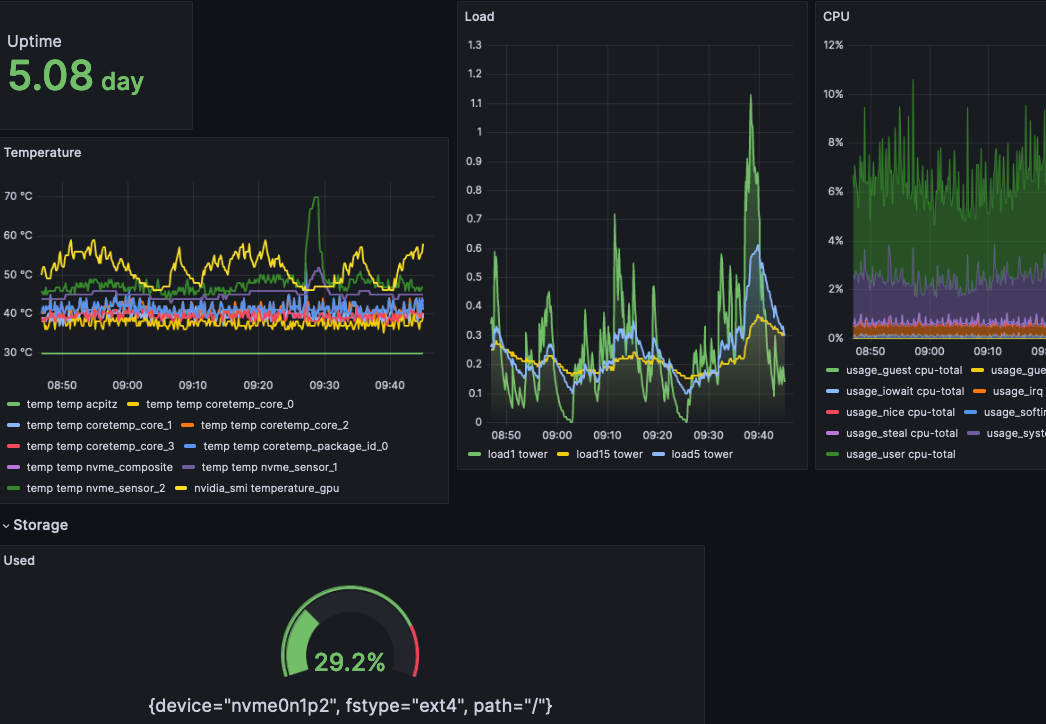

Before this Terraform + Ansible + Docker stack, I didn’t really have a monitoring setup. My hardware resources were a bit fluid and a lot of the standard monitoring ecosystems have a bit of a learning curve. It’s not just this management stack that allowed me to set up proper monitoring but it has been made much easier with it.

I first tried Prometheus but bounced off of it. That isn’t intended as a slight, Prometheus is a very powerful tool, but it’s not the one I settled on.

The spur for the development of what became my final setup was trying to get insights into my network with stats from my router. Pfsense has a Telegraf plugin for dumping a range of stats to InfluxDB for querying, this was my first foray into both. Looking a bit further into InfluxDB, I found that Home Assistant will also natively dump state information over time to InfluxDB.

For a bit of background, InfluxDB is a Time-Series Database or TSDB. InfluxDB is not structured relationally like MySQL or Postgres, instead it’s a bit closer to NoSQL. Influx has buckets that can be written to, each record that you write is structured as a time-value pair with a variable number of other tags and metadata.

Influx has native functionality for presenting data in dashboards and firing alerts but I had heard of Grafana and wanted to see how easy it was to integrate. Grafana is great, you can set up all sorts of data sources to show data from including Influx and your standard SQL databases.

Grafana is good, not only in of itself, but also because it separates presentation from the storage layer. In the Telegraf configuration you define which bucket the data will go to and in Grafana you then reference these same buckets. As a result, the database itself can be ephemeral, you don’t want it to be because then you will lose data, but losing the database is just the data, not the (very pretty) dashboards and alerts.

Git + Jenkins Link to heading

Another set of services I have managed to set up recently are Gitea and Jenkins. A local Git server is something that has been in the back of my mind for a while, I have manually backed up my code from Github in the past but hosting it locally is really doing that properly. I ended up going with Gitea over something like Gitlab for resources sake, Gitea is very lightweight. Although Gitlab has a lot of bells and whistles like integrated CI/CD I wanted to play around with using a separate Jenkins instance for this.

Gitea has very powerful mirroring capabilities, able to both push and pull from other repositories, in my case on Github. My setup is to have all of my working copies use my Gitea instance as their sole remote so code is pushed there first. From here, Gitea is configured to push changes to Github for all of the repositories. The result is basically transparent to before, I push my code from my laptop and it ends up in Github, but I now have a local server that acts as a backup.

I have also started using one of the features of Gitea that, when I installed it, I didn’t even realise it had - package repositories. Gitea can function as a repository or index for artefacts of all sorts of code, from Docker containers to C# Nuget packages, to Python PyPi modules. I have primarily been using the docker repository so far, I am really starting to feel the power of this in conjunction with my Jenkins instance.

Jenkins is one of the services that has required the most fiddling, there are a lot of moving parts. I have played with a couple of different architectures and have decided that a split approach may be the best in the long term. This is due to its flexibility, it’s a very mature piece of software that can be used in many different ways.

controller only Link to heading

My first approach was to have a very low footprint instance, doing all work on the controller. This quickly seemed unscalable, I didn’t like having to pack all of the dev dependencies into the controller image as well as possibly having project artefacts lying about on the controller.

Bit of context, Jenkins discourages this approach for (very valid) security reasons. This approach means that the actual CI/CD work, building, testing and deploying code, is done in the same process that is controlling Jenkins. Because the definitions of what your CI/CD pipeline looks like can be defined by users in the projects, this means that anyone with access to code repositories being used by Jenkins could mess with the pipeline and do arbitrary things to the box running Jenkins itself. There basically aren’t any security barriers at this point which could be a nightmare depending on what other projects Jenkins is running.

agents Link to heading

A more stable approach is to use agent nodes. This allows the controller to do no work itself, it has another “box” that it co-ordinates running the pipeline on. Output from the pipeline is streamed back to the controller for display to the user in the UI, it’s basically transparent to the user. From a security perspective, this separates the brain of Jenkins from where the nitty gritty work is actually getting done. More separation can be put between projects by making them work on different nodes. However this is the tip of the iceberg, modern Jenkins lets you do some crazy stuff with this approach.

Using pipelines, different parts of the CI/CD job can transparently happen on different nodes, all coordinated by the controller. If you need to test on multiple platforms it’s as simple as having a Windows box and a Linux box, the pipeline can have stages that use both.

From using just the controller, I decided that I would use a worker node that had the required dev dependencies baked in. This approach worked much better and also made pretty good use of resources, Jenkins can be configured to sleep the node when there’s nothing to do and only wake it up when there’s a job waiting.

This approach worked great, I was using Jenkins to build its own agent and push this to my Gitea container repo. This agent image would build my code for me and spin down when it wasn’t being used. However, there was a problem, when I tried to build one of my Python projects, I found that I was using a version of Python that was newer than the one that had been installed into the Ubuntu-based agent image.

more containers Link to heading

There is a final evolution to this architecture, though. Bearing in mind that I am already running both the Jenkins controller and agent in containers, you can continue down the rabbit hole, running docker-in-docker, stacking containers on containers until all around you, all you can see are containers.

I mentioned before that with Jenkins pipelines, you can have different stages on different agents connected to the controller. However, you can also have each stage run in a container. This solves my previous Python version problem, I can just point that pipeline stage at the newer Python image on Docker Hub.

This approach is very cool, and not that hard to set up. Docker can be controlled over the wire with a TCP socket. Docker can also be run from within a container with the “dind” image which needs to be run privileged. Ultimately, it’s as easy as adding a dind container to the compose file, setting a few environment variables on the controller and letting it share a volume with the dind for certificates.

Backups Link to heading

This Terraform, Ansible, Docker stack I have been describing (… T.A.D?) is great for running services but if they aren’t backed up, are they really running at all? My approach to this for a while was a bit ad-hoc. Using pgAdmin to create backups of databases manually, all of that sort of stuff.

As my array of services expanded, though, this wasn’t going to scale. The solution was another Ansible role. My backup role uses the same inventory that defines which services will be deployed on which resources to identify where backups need to be made. It relies on the Docker module to run commands in containers and the fetch module to pull these backups back to my laptop.

The actual steps depend on the service, some are just databases, some have some filesystem locations that need archiving as well. For example, below is the backup script for Gitea.

- name: Set dump names

set_fact:

db_dump_name: gitea-{{ ansible_facts['hostname'] }}-{{ ansible_date_time.iso8601 | replace("/", "-") | replace(":", "-") }}.sql

data_dump_name: gitea-data-{{ ansible_facts['hostname'] }}-{{ ansible_date_time.iso8601 | replace("/", "-") | replace(":", "-") }}.zip

- name: Stop services

community.docker.docker_compose:

project_src: $HOME/{{ gitea_ws }}

stopped: true

services:

- server

- name: Archive Gitea data

community.general.archive:

path: ~/{{ gitea_ws }}/data

dest: ~/{{ gitea_ws }}/backup/{{ data_dump_name }}

format: zip

- name: Dump Gitea database to file

community.docker.docker_container_exec:

container: gitea_db_1

user: root

argv:

- /bin/bash

- "-c"

- "pg_dump --format=plain gitea -U gitea -E UTF8 -f /backup/{{ db_dump_name }}"

- name: Start services

community.docker.docker_compose:

project_src: $HOME/{{ gitea_ws }}

services:

- server

- name: Enumerate backups

find:

paths: ~/{{ gitea_ws }}/backup/

file_type: file

patterns: "*.sql"

register: filelist

- name: Take ownership of backups

become: true

file:

path: "{{ item.path }}"

state: file

owner: aj

group: aj

mode: "0664"

with_items: "{{ filelist.files }}"

- name: Pull data backup

ansible.builtin.fetch:

src: ~/{{ gitea_ws }}/backup/{{ data_dump_name }}

dest: ~/{{ backup_ws }}/

flat: yes

- name: Pull database backup

ansible.builtin.fetch:

src: ~/{{ gitea_ws }}/backup/{{ db_dump_name }}

dest: ~/{{ backup_ws }}/

flat: yesYou can see that we first stop the service itself so that the data is in a static state when we save it. From here we first zip up the data folder, this is the folder that we bind mount into the Gitea container. Sometimes I’ve used named volumes instead of bind mounts but the process isn’t really any harder. Next, we dump the database itself. You can see that we write this dump inside the container, but in reality /backup is bound outside of the container so we can pull it from the host. We restart the services now, the saving is done and they don’t need to stay down while we process and pull the backups. The Take ownership step is interesting, you can see that we run the Docker database command as root, as a result, the output file is owned by root. In order to not faff about with fetching as root and all of that, we chown everything in the backup folder to the non-root user. Finally, we pull everything back to my machine.

This has made my backups more consistent, no more making sure we get the same settings in pgAdmin when making backups, no manually faffing with containers to pull some folders out, no excuses to skip services.

Thoughts + Favourite Bits Link to heading

Having a single git repo with all of my infrastructure defined gives a lot of peace of mind. It is the source of truth allowing me to see how my infrastructure has changed over time. It gets me a lot closer to workflows like Git-Ops, but at the moment I’m not too fussed about having my Terraform and Ansible run by Jenkins.

The backup workflow provides a lot of stability, making sure that no matter where the services are running they are monitored and snapshotted periodically.

There are plenty of ways to achieve what I have working, but this pattern that I have used is a pretty good one, if I do say so myself.